Categories

- Handmade Katana, Samurai Swords

- Handmade Iaito Swords

- Shogun PRO Blades

- YariNoHanzo Handmade

- Handmade Bokken

- Collectible mini katanas and Samurai pens

- CUSTOM SWORDS IN STOCK

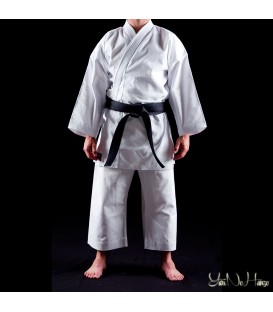

- Keikogi - Clothing

- Hakama

- Tabi and accessories

- Samurai Swords Accessories

- Maintenance

- Bokuto / Bokken

- Tameshigiri

- Padded Swords

- Bags

- Budogu & Ningu

- BARGAIN CORNER

- BOGU - KENDO ARMOR

- DISCIPLINE

- TRAINING SET | BIG DEAL

- Clothing & Accessories

- Decorative Swords

- BUDOSUMMER 2025

- KATANA SHINKEN - 18TH ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL EDITION!

- KATANA AVAILABLE ON ORDER ONLY

New products

-

NAMI 18TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION XL

YariNoHanzo turns 18 years old!We are pleased to present to you on this...

£690.00 -

Togakure Shinobigatana | Handmade Katana Sword | ED.18 YEARS

YariNoHanzo turns 18 years old!We are pleased to present to you on this...

£690.00 -

Kamakiri | Handmade Katana Sword | ED. 18 YEARS

YariNoHanzo turns 18 years old!We are pleased to present to you on this...

£690.00 -

Sakai | Handmade Katana Sword | ED.18 YEARS

YariNoHanzo turns 18 years old!We are pleased to present to you on this...

£690.00

Top sellers

BLADE MAINTENANCE

As every other kind of sword, the carbon steel, of which the blade of the katana is made, requires specific attentions to prevent it from getting rusty. According to tradition, first of all we have to disassemble the katana and to separate it from the handle (koshirae), at this point we have to spread it with a specific dust derived from the stone that was used during the last polishing through a pad beaten against the blade with small strokes that release a small amount of dust.

This dust is then removed from the sword by a rice paper, hold tight on both sides of the samurai sword, rubbed down the blade from its base to its tip. After that we have to use another rice paper, soaking it in a peculiar clove oil called Choji and rubbing it on the blade because the oil will protect it from oxidation. These procedures were of great importance in the ancient Japan where the climate, humid both during the summer and during the winter, facilitated the oxidation of the katanas not well groomed.

Nowadays many people still recommend the employment of the ancient techniques, thinking that since they have worked for centuries, they must be efficient.

Nevertheless two among the best contemporary gunsmiths, the Canadian Albion, specialized in the forging of western medieval swords and Yarinohanzo, specialized in Japanese katanas, suggest the use of a modern synthetic oil, the Ballistol, thought for fire-arms, which creates a protective film and, insinuating itself in the steel pleating, hardens and gives a lasting protection, probably better than the traditional techniques; it also allows a minimal maintenance (more or less every six months).

Of course if the katana is used and it comes in contact with anything, it must be oiled again at the end of the practice. The technique is easy, we just need to get a rug, oil it and rub it a couple of times on the blade always following the handle-tip trend.

Sometimes the rust can appear if the blade is not well groomed. There are two kinds of rust: the active one and the stable one; the first kind is reddish and it’s the most dangerous because, if not promptly removed, it tends to advance until it has damaged the katana irreparably. The second kind instead is far less dangerous, it looks like black stains and it can remain on the sword because it doesn’t advance with time. The technique employed to remove both kind of rust is called polishing process and is usually carried out by experts.

A polishing process accurately carried out, in addition to remove the rust from the blade, restores its edge.

In centuries the many polishing processes carried out tend to remove the external layers of the blades, making it lighter and depriving the edge of its original characteristics. Then wide stains start to appear due to the total removal of the external hard steel (kawagane) in some points, exposing the soft steel of the blade heart (shingane). At this point the katana is defined as “tired”.

The original katanas are always sharpened, indeed removing the edge or making it blunt usually means ruining the samurai sword since the removal of the edge implies taking out numerous external and hard layers, aging the blade and, sometimes, its renovation it’s not possible anymore. Clearly not each sword ages in the same way and some school, like for example the Rai school, add an exterior steel layer (kawagane), very hard and thin, in order to confer a very strong and lasting edge to the blades. On the other hand this kind of katana is going to age quickly as a consequence of the many polishing processes that inevitably remove the thin external layer (kawagane) exposing the soft inner heart (shingane).

Other schools add thicker coverings, making the samurai sword more resistant to the polishing process. We have to say more or less the same thing for the section of the blade: some katanas have an edge composed of a thick block made of hard steel while others are composed of two or more steel layers softer and softer (see the previous explicative graphic) but these blades are more sensitive to the polishing process. In some cases, the experts tend to consider the shingane stains (meaning the areas in which the external hard steel has been removed and where the soft steel of the blade heart is exposed) a typical characteristic of a particular school (as the Rai one) rather than the sign of the katana aging and that’s true when the external layer, being extremely thin, shows the shingane stains in almost all the exemplars survived to this day.

We must not ABSOLUTELY touch the sword tang (nakago), meaning that part of the blade that is situated inside the handle. It’s always more or less rusty and it’s used, together with other parameters, to date the katana and to confirm its authenticity. A samurai sword with a polished tang (nakago) looses at least half of its original worth. The tang can only be oiled but I can never, in any case, be rubbed off.

You can find many different models of katanas for sale on these websites:

Katanamart UNITED KINGDOM

Katanamart SPAIN

Katanamart FRANCE

Katanamart GERMANY